- Artifacts of Being

- Posts

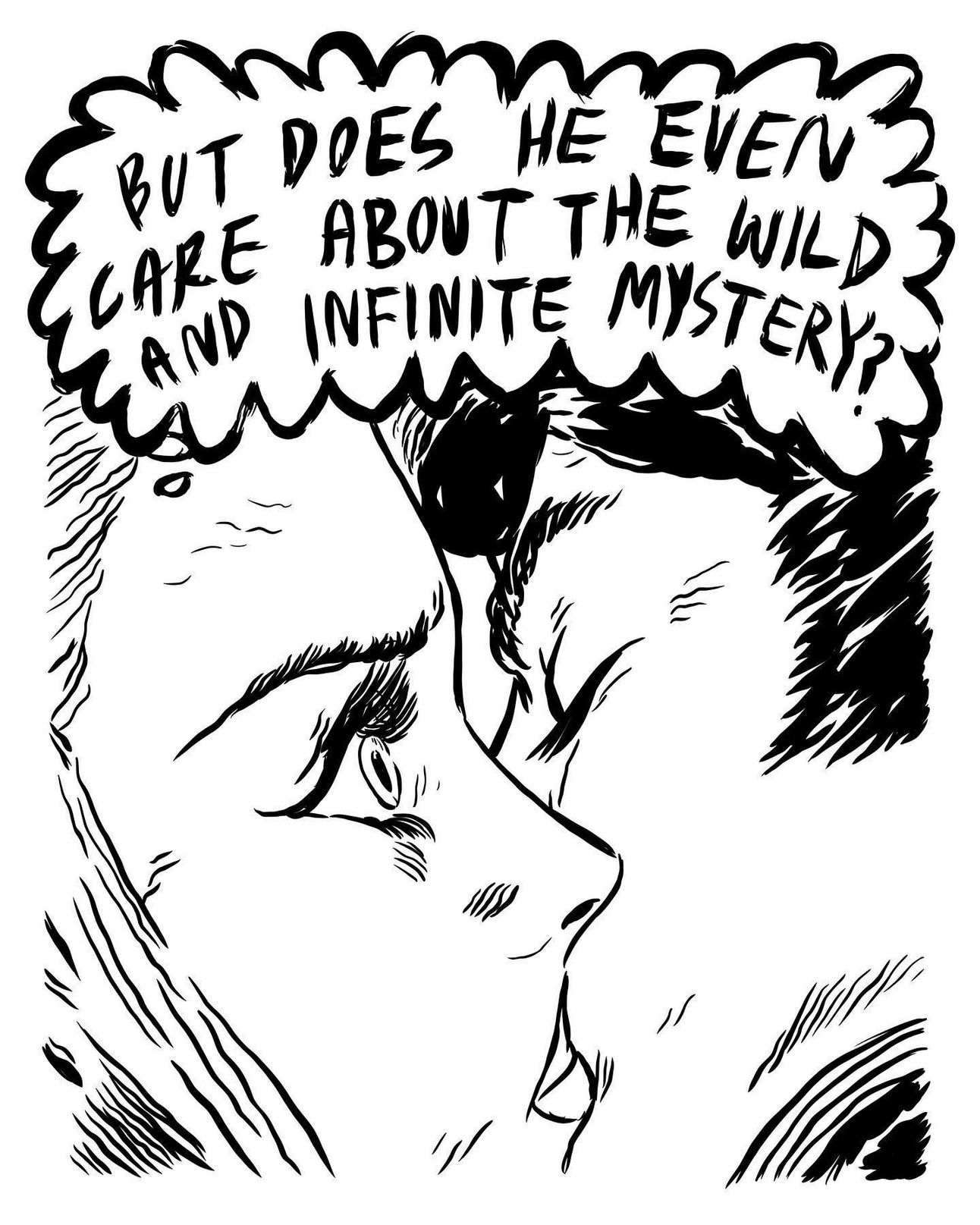

- The Wild and Infinite Mystery

The Wild and Infinite Mystery

Logic and sermons never convince, the damp of the night drives deeper into my soul. — Walt Whitman

Some of us are forced by our own sensibilities to question the nature of reality.

Some of the questions are probably knowable:

What is everything made of? What is the substrate and structure of the universe?

What is the origin of consciousness, and how can it emerge from matter? What else could it emerge from?

Is everything in the universe predetermined?

And some of the questions are probably unknowable:1

How could time ever end, but how could it not?

How could space ever end, but how could it not?

Why is there anything at all?

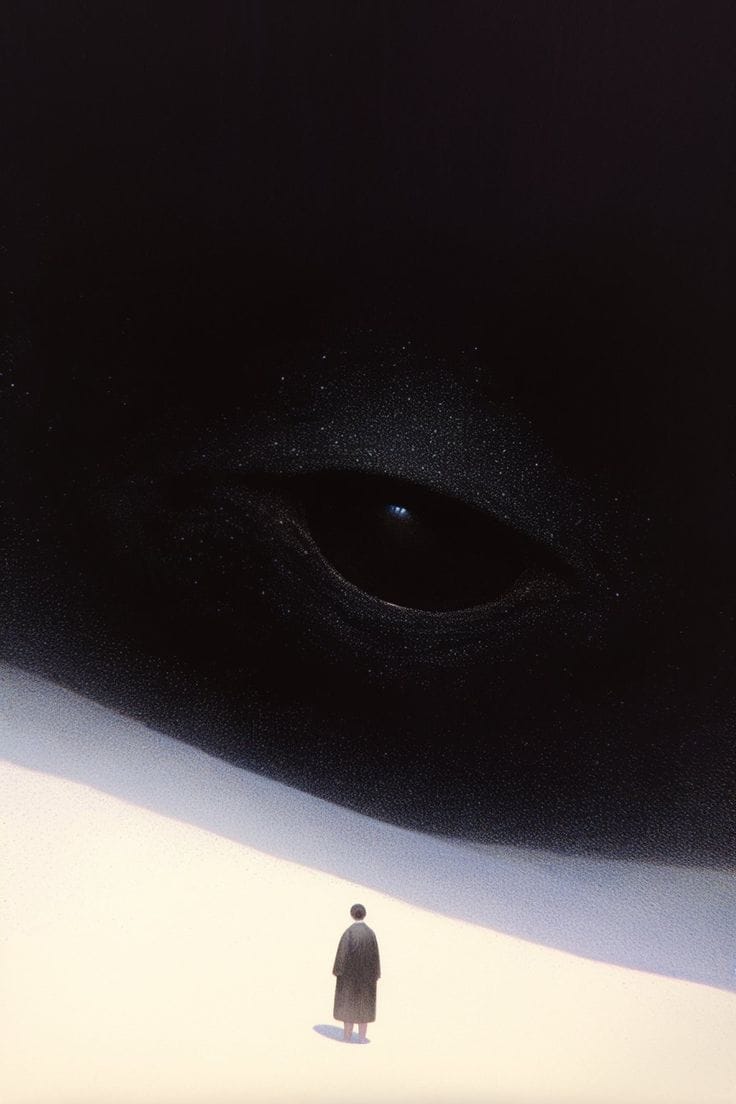

These questions leave me with vertigo and wonder—which I sometimes enjoy, and sometimes don’t. It just happened to me while thinking about this, but I don’t know if it’ll happen to you just reading about it. Maybe you have to stop and think about it. We can start with something immediate: this moment, this text, the light from your screen. And then pull back: the room, the building, earth spinning in space. The solar system, the galaxy, the universe stretching billions of lightyears. And then... what? Something gives rise to you and everything around you, in every direction you can conceive of, and that thing is unknown. And something likely gives rise to it. Onward, all the way up or down or out. But stepping back even further: none of this had to exist at all. There could have been nothing. No space, no time, no matter, no consciousness to wonder about it. No where, no when, no that, no now. And yet here's everything. What a strange reality.

Maybe it’s beyond human comprehension. Maybe the frame of conception is off. Maybe lots of things—but it’s astounding that I can’t even imagine what an answer would look like.

Over the years, I’ve developed a deep reverence for mystery. Attention to this mystery has helped me connect more deeply to nature—to myself and others and everything around me—and made me feel more at home in my existence as a human being.

The world is fun and familiar, and healthful, and unbelievably refreshing and lovely. And it is the theater of the spiritual. . . it is the multiform, utterly obedient to a mystery.

This is everyday, sustained ecstasy, drinkless drunkenness, a deep and abiding—if quieter—appreciation of just how wondrous the world is and how fortunate we are to be alive and taking it in.

Many things2 pointed me toward it.

1. Podcast | The Tim Ferriss Show: Professor Donald Hoffman

When you've always favored material explanations of the world, it takes some serious work—and people with serious credentials—to shake up your intuitions.

Most of us believe that the physical world, or matter, gives rise to consciousness (e.g. a brain made of neurons and chemicals produces our inner experience of being alive). Of course, right?

But Donald Hoffman argues that it is consciousness that gives rise to the physical world.

Hang with me here:

After decades of research, he argues that space, time, and physical objects are not the building blocks of reality, nor the inherent processes of the universe. Instead, he says they are a user interface we experience, shaped by evolution to help us survive. (If seeing nature’s underlying reality was too complex or energy-intensive, evolution3 may have favored creatures who see a simpler, more practical version of the world—like using phone apps without awareness of the code underneath.) But even if we question whether the external world exists as we perceive it, Hoffman explains that conscious experiences themselves—pain, joy, colors, thoughts—are undeniable. And he reasons that consciousness might be the fundamental reality, with space, time, and physical objects emerging from deeper networks of conscious minds. He then develops mathematical models to explore how this might work. |

This episode is quite nerdy and mind-bending! :) But the point is this: regardless of whether or not Hoffman is right, his deeply counterintuitive position exposes the limits of our current explanations and reveals how much we take for granted about what’s really going on in the universe, and within our own bodies and experiences. For me, it’s a humbling reminder that I simply don’t know; I can’t be certain of my most foundational assumptions. |  |

2. Insight | The Moon’s Mystery is My Own

I listened to Hoffman’s episode late one evening in November of 2022, while driving from Denver to Kansas. In the preceding weeks, I’d been grappling with a visceral, unsettling confusion about what kind of thing I am. As I’ve written before, I felt like a random, strange thing, floating through space, tossed by forces I don’t understand.

And this confusion was directed only at myself, not anyone or anything else.

But on that November night, the swirl of theory and fatigue primed me for an experience that would help me transform those feelings at their root.

Dazed from everything I'd been absorbing, I looked up at the moon. I felt a familiar awe at how it hangs there, suspended—a reminder that we live on a rock hurtling through space. But this time, I wasn't just amazed by the moon; I was genuinely baffled that it existed. (I wish I could drop you directly into that feeling—something utterly ordinary becoming utterly mysterious.)

And then a realization washed over me: the mystery that underlies the moon's existence is identical to the mystery underlying my existence. It’s as inherent in the moon as it is in me. The moon is also a seemingly random, strange thing floating through space, tossed by forces beyond understanding. We share the same position in the universe: existing against the odds, from unknown origin, composed of the unknown.

I'm no less mysterious to myself than before, but I'm not alone in it; I'm accompanied by everything else I can think of. All of us mysterious together, united in the improbability of existence and the mystery of where we came from, what we exist in, and what we’re made of.

That anything exists at all does seem to me a matter for the deepest awe.

3. Excerpt | From the Tao Te Ching

The Tao Te Ching, one of the world’s most influential spiritual and philosophical texts, takes as its subject the Tao: an indescribable, mysterious force underlying all existence; the source of all things, formless and beyond words.

The book begins:

“The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao.

The name that can be named is not the eternal name."

If we can attach any qualities to the mystery, we've already turned away from it and replaced it with concepts. I’m skeptical when anyone claims to know any specific attributes about it; I suspect that, as my friend Neha once put it, “they’ve made the infinite finite.”

4. Quote | By Anthony de Mello

In his incredible book Awareness, de Mello writes:

The final barrier to God is the word ‘God.’

UGH. Delicious.

We get so caught up in prescriptions made in God's name, and the painful associations they can carry, that we miss the underlying experiences available to us. It reminds me of Parker Palmer’s poignant words: "How did so many disembodied concepts emerge from a tradition whose central commitment is to 'the Word become flesh'?"

Growing up, I didn’t believe in God as described in any of the major religions. To my mind, they purported to know4 something far, far too mysterious to understand. And the frame that God is Love never quite helped me relate to religious texts or people; it still felt too definitive—a leap.

But when I started exploring the framing that God is Mystery, religious expressions began to make a lot more sense. I began recognizing myself in the writings of mystics, nuns, saints, monks—and animals and insects and trees—and space and stars (and not just for the stardust we share).

5. Poem | Mysteries, Yes by Mary Oliver

Truly, we live with mysteries too marvelous

to be understood.

How grass can be nourishing in the

mouths of the lambs.

How rivers and stones are forever

in allegiance with gravity

while we ourselves dream of rising.

How two hands touch and the bonds will

never be broken.

How people come, from delight or the

scars of damage,

to the comfort of a poem.

Let me keep my distance, always, from those

who think they have the answers.

Let me keep company always with those who say

“Look!” and laugh in astonishment,

and bow their heads.

Before mystery became central in my life, I thought a lot about determinism and materialism: I am a body of chemicals—a machine acting on programming designed to propel me to share my genes. Everything is just molecules and atoms working on an algorithm.

I believed that it’s wiser to confront reality, no matter how unsettling, than to be soothed by falsehoods.

And gradually, subtly, and without realizing it, I came to believe that truth must sting—and that I was smart for exposing myself to it and enduring it. And I was quietly disassociating from my life, watching it unfold from behind glass, confused about whether I should hold anyone accountable for anything. As William James writes, “The idea that the future is inflexibly determined, that one’s own acts are necessary links in the causal chain, produces a kind of mental coldness, and a tendency to lie down and let things slide.” And then one day, at last, I saw through it: I’m letting metaphysical certainty drive me mad — and I’m not actually certain!6 |  Jerzy Głuszek |

Not only that but, to the extent that I can choose what I believe, I’d rather focus on nourishing ideas than philosophies that erode my capacity for joy, connection, and meaning. It turns out that when I'm stripped and facing fire, I'd rather know happiness than truth.

Here’s what I’ve come to believe about philosophy and wellbeing:

We shouldn’t let speculative philosophical positions jeopardize our wellbeing.

Even if there is a definitive philosophical truth that jeopardizes our wellbeing, it may not be wise to confront it until—if ever—we’re ready to face it without much harm.

There's so much truth to explore, and perhaps the wisest thing we can do is to seek the truths that bring us peace, allow us to live full lives, and honor the precious brevity of our existence.

To see the mystery,7 I needed to loosen my grip on intellectual certainty. Now, I think mystery captures the deepest truth we can express about existence—and it leaves me more open in how I think about and honor all that is.

In what is probably the most serious inquiry of my life, I have begun to look past reason, past the provable, in other directions. Now I think there is only one subject worth my attention and that is the recognition of the spiritual side of the world and, within this recognition, the condition of my own spiritual state. I am not talking about having faith necessarily, although one hopes to. What I mean by spirituality is not theology, but attitude.

There is a kind of bravery to our condition, I reckon: brought into being without an explanation, in a potentially infinite and apparently dead universe, and expected to just get on with it as though nothing strange is going on . . . well it is, and it's all right to have a meltdown about the whole affair from time to time, faced with the pressures of modern existence, trying to be a good human and a good worker and a good son/daughter/parent, trying to be a good citizen, trying to be wise without condescension but uninhibited without recklessness, trying to just muddle through without making any silly decisions, trying to align with the correct political opinions, trying to stay thin, trying to be attractive, trying to be smart, trying to find the ideal partner, trying to stay financially secure, trying to just find some modest corner of meaning and belonging and sanity to go and sit in, and all the while living on the edge of dying forever. We're all in the same strange boat, grappling with the same strange condition. But it isn't quite so scary if we all do it together.

Lucy

While making this post, I learned that the Ancient Greek philosopher Anaximander wrote about the "apeiron" — the infinite, boundless, or unlimited fundamental principle or origin of everything. It turns out that many traditions have pointed to this concept:

Date (Approx.) | Tradition | Concept | Core Idea |

|---|---|---|---|

c. 2600 BCE | Ancient Egypt | Nun | Primeval, infinite waters from which the world arises |

c. 2000 BCE | Mesopotamia | Tiamat / Abzu | Chaotic primordial waters or void; origin of gods and cosmos |

c. 1500–800 BCE | Vedic India | Brahman (nirguna) | Infinite, formless, transcendent reality beyond attributes |

c. 1000–800 BCE | Hebrew (Biblical) | Tohu va-bohu | “Formless and void”; the shapeless state before creation (Genesis 1:2) |

c. 1000–800 BCE | Zoroastrian Persia | Zurvan / Infinite Time | Infinite time or primordial force preceding good and evil |

c. 1000 BCE | Ancient China | I Ching – Taiji | The undifferentiated totality before yin and yang split (cosmic unity) |

c. 800 BCE | Homeric Greece | Oceanus / Chaos | Mythical representation of the all-surrounding, unformed origin |

c. 600 BCE | Ancient China | Dao (Tao) | The ineffable, eternal source of all things; ungraspable and formless |

c. 610–546 BCE | Ancient Greece | Apeiron (Anaximander) | The boundless, indefinite, eternal origin of all opposites and beings |

c. 500 BCE | Pythagorean Greece | The Monad | Unity as the first principle; undivided and generative |

c. 500 BCE | Jain & Buddhist India | Ākāśa / Śūnyatā | Space or emptiness as infinite, supportive ground of all phenomena |

c. 300 BCE – 300 CE | Neoplatonism (Plotinus) | The One | Absolute unity, beyond being and thought; source of all levels of reality |

c. 100–300 CE | Christian Mysticism | Godhead / Uncreated Light | Transcendent divinity beyond all categories and names |

c. 900 CE | Islamic Philosophy | Al-Haqq / Wahdat al-wujud | The Real; oneness of all existence in God |

Oral, Prehistoric | Indigenous Traditions | Great Spirit / Dreaming / Wakan Tanka | Infinite, animating mystery or principle of life and connection |

And, in modern science, the quantum vacuum or singularity — everything from nothing, and undifferentiated state.

1 We’ll probably always be stuck . . . in the infinitely receding horizon of our ability to know or understand it. — Anika Harris

2 Certainly more things than I could count. Taoism (which felt like it captured truth about the universe more intuitively than anything I’d come across), Mary Oliver, thinking (the sense that neither words nor science can capture reality — that reality itself is beyond comprehension), feeling (like an alien in existence; like a robot in determinism and materialism), concepts like panpsychism (that provocatively shake up intuitions), philosophy of science, metaphysics, experiences with meditation, etc.

3 (It's a little confusing, because evolution presupposes the reality of space, time, and physical processes. But he's basically saying: evolution is the best tool we have from inside the interface to understand why we see what we see. But it doesn’t mean the interface is ultimate reality.)

4 The passion for truth is silenced by answers which have the weight of undisputed authority. ― Paul Tillich

5 I wasn't one of those people who could believe determinism without being crippled by it.

6 And certainty is neither the spiritual spirit, nor scientific spirit as Walt Whitman describes it: “I like the scientific spirit—the holding off, the being sure but not too sure, the willingness to surrender ideas when the evidence is against them: this is ultimately fine—it always keeps the way beyond open—always gives life, thought, affection, the whole man, a chance to try over again after a mistake—after a wrong guess.”

7 Again, I’ll quote a letter from my high school Humanities teacher, Mr. Davis: “Whatever we have studied this year, it only became the ‘stuff’ of a humanities class when there was a mystery present that could not be quantified, for to quantify any object, event, experience, or person is to take the mystery out of it. Thus another paradox: we cannot be fully human if we do not analyze both the world around us and ourselves (it’s the only way we can ever construct a place for living that is even slightly tolerable); but if we fall prey to the over-analysis monster—if we take the mystery out of who we are—we make of ourselves nothing more than rats in a maze: scrawny little creatures scuttling from wall to wall in search of ever smaller bits of cheese—finding, chewing, gulping, belching—then scuttling off around the corner to do the same thing over and over and over again. And over and over and over. . . . Mystery, however, not only makes life tolerable, it makes it worthwhile. So let us praise mystery. Let us wallow in it. Let us drink deeply from the wonder that is its confusion and awe and beauty and pain and laughter. Most importantly, let us drink deeply from ourselves—for we, too, are mystery.”