- Artifacts of Being

- Posts

- Your Place in the Family of Things

Your Place in the Family of Things

I will no longer find myself in life as in a strange garment — W.S. Merwin

Not all artifacts are created equal. Today’s pieces—each tied to the theme of our inherent belonging in the universe—have been true lifelines for me.

Sometimes when I’m down, I feel like a random, strange thing, floating through space. Out of place, disconnected, disassociated, and even robotic. I feel tossed by forces I don’t understand, confused about what kind of thing I am, and confused about the source of my consciousness or my actions.

Today’s artifacts aren’t just philosophical musings; they’ve helped me with genuine ailments, and I’ve turned to them to regain connection to my body and relax into existence.

1. Poem: Wild Geese by Mary Oliver

Mary Oliver single-handedly changed my life1 and deepened my connection to the natural world. Through her, I discovered a love of poetry, a deeper reverence for all that is, a sense of oneness with (and surrender to) the processes of the world and—through all of that—a greater sense of belonging and comfort in my own skin.

the soft animal of my organic body - not my robot machine

my place in the family of things - not a glitch, out of place among all that is native

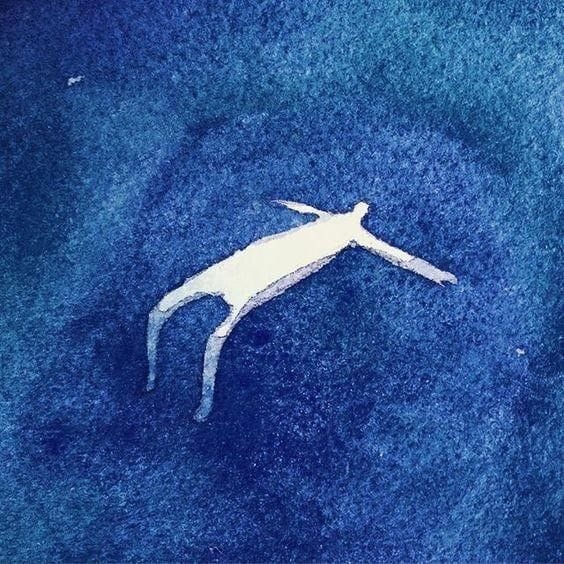

"Giraffe Nocturne", watercolor, by Alison Nicholls

2. Legend: Siddhartha Calling the Earth to Witness

The closing line of this tale—from the final night before Buddha’s enlightenment—reminds me of my place in the family of things. Here's how I remember the story:

On the night of his enlightenment, after days of meditating under the Bodhi tree, Siddhartha sat quietly in deep stillness.

Mara, the god of desire and illusion, sensed that Siddhartha was nearing enlightenment, so he appeared before him to disrupt his path. He sent his daughters to tempt Siddhartha with passion and desire, but Siddhartha was unmoved. Mara sent armies and lions to instill fear and doubt, but these attempts failed too. Then, he reminded Siddhartha of his past and his responsibilities, hoping attachment would pull him away. He planted seeds of self-doubt, whispering that Siddhartha was unworthy of awakening, and conjured terrifying illusions to disrupt his presence. Still, Siddhartha remained unshaken.

As a final challenge, Mara declared: “I have my armies, my daughters, my power—all of them bear witness to my authority. Who will bear witness to yours?”

In response, with his eyes still closed, Siddhartha reached down and touched the earth.2

When I feel separate from the world, unworthy of it, as if I don't belong here, I remember Buddha's hand. I exist. I don't need more justification or permission. I am woven into the fundamental structure of the universe,3 as are my pursuits; I am as natural and inherent as any bird, and my pursuits as natural and inherent as any nest.

3. Concept: The Wave is the Ocean

We are inherent to the universe. “We do not ‘come into’ this world; we come out of it, as leaves from a tree. As the ocean ‘waves,’ the universe ‘peoples.’ Every individual is an expression of the whole realm of nature, a unique action of the total universe.” — Alan Watts If we don’t realize this, we experience pain. “If you don't become the ocean, you'll be seasick every day.” ― Leonard Cohen To fully realize and surrender to this is to experience enlightenment. “Enlightenment is when a wave realizes it is the ocean.” — Thich Nhat Hanh |  by Andrea Serio |

When we fear death, it helps to remember:

“The body of a wave does not last very long — perhaps only ten to twenty seconds. The wave is subject to beginning an ending . . . and the wave may feel afraid or even angry. But the wave also has her ocean body. She has come from the ocean, and she will go back to the ocean. [For fear to disappear],5 the wave can go back to herself and touch her true nature, which is water.” — Thich Nhat Hanh

“Allow the ocean to hold you.” — Gangaji

4. Video: from TV Show This is Us

This Is Us isn’t the first show I'd associate with Eastern philosophy, and yet there’s this.

The show is known for stirring emotions, and this speech (starting at 1:50) is no exception.

5. Meditation: From My Childhood, Where is Me?

| When I was 9, or maybe 11, I would lie in bed for long stretches of time, perfectly content, and at some point I’d close my eyes and ask myself, What am I? I’d imagine a little camera going inside me, searching for me. Where is me? Where is me? Eventually, I’d start to feel some sort of shift — an internal knowing that me is a deeply mysterious thing, impossible to name, and almost impossible to feel for more than a few moments. When I’d open my eyes, things would feel a little surreal. I’d feel a little scared, a little larger, and curious to return to that state and question in the future. |

Now, at 33, I’m more acquainted with that state, but I still have no answers about the source of me. That uncertainty doesn’t scare me as much when I realize that the foundation of everything is a mystery. It’s astounding and mysterious that I have consciousness, but it’s also astounding and mysterious that the planet exists, the moon, the universe; whatever existence is, whatever the universe hangs in, it’s all sourced in mystery.

—

When I, a secular person, first picked up Mary Oliver’s book Devotions, I dismissively thought, “ugh, devotion to what?” Then I read the book — an extraordinary depiction of our sacred connection to nature — and finished with the realization that, if I am devoted to anything, it is to resting in awe of that. And I agree with Mary who, in response to the sacred, wrote in her poem Forgive Me:

If I were a perfect person, I would be bowing continuously.

Lucy

Soft Darkness by Coralie Huon

1 I feel like I’ll say this phrase in Artifacts of Being more than I do anywhere else. But that’s also sort of the point, right?

2 My boy Siddhartha didn't claim a divine right, call upon disciples, or argue his worth; he just touched the planet.

3 I’m tempted to get into determinism—are we so fundamental to the universe that our place here was inevitable, that it couldn’t have been otherwise?—but I don’t know if it’s true, and I worry about the impact of believing it. But I find it powerful, grounding, integrating enough that, even if it could have been otherwise, it isn’t otherwise. We are here.

4 We hear this word all the time, but I find myself wanting to define it. Enlightenment, or awakening, isn’t an intellectual idea but a felt experience. It’s when your sense of self dissolves into a sense of the universal. Brief moments of this disillusionment are called satori in Japanese. I’ve felt this visceral, reality-bending experience a handful of times in my life. It feels like an instantaneous shift—an intuitive, unmediated insight into the nature of life. Or rather, the nature of everything. Satori is often considered a milestone toward deeper, more lasting enlightenment, called kensho.

5 I’m still working to internalize this — to get in touch with the ocean body in a way that helps me not fear death — but I can only glimpse it, and then it’s gone.