- Artifacts of Being

- Posts

- The Work Your Soul Must Have

The Work Your Soul Must Have

Ask me whether what I have done is my life. — William Stafford

Thomas Merton writes:

“If you want to identify me, ask me not where I live,

or what I like to eat, or how I comb my hair,

but ask me what I am living for, in detail,

ask me what I think is keeping me from living fully

for the thing I want to live for.”

I find this quote so sobering, and want to take its questions seriously: What do I want to live for? What keeps me from living fully for it?

Without thinking too hard about it, what comes up for you?

For me, it’s a desire for a particular kind of work. A life’s work—immersed in philosophy, spirituality, poetry, and art about the human condition. Making sense of existence and how to be more at ease in it. Connecting with people who love ideas and who challenge my thinking. In perpetual conversation, creation, and bohemian play.

And what keeps me from living fully for this? Why am I not learning with abandon and, with that, understanding more, creating more, and contributing more meaningfully?

Over the past few months, I’ve been excavating my deepest aspirations and conflicts around work, and considering whether a life's work should also be a professional work. This entire domain often feels like a slippery ball, one I can barely think about before getting ambiguated by various paths and insecurities.1

Getting my arms around the ball has taken a lot of work. I’ve discovered that many of us are surprisingly disconnected from what we actually think about, or want from, hugely important domains2 of life—like how to shape the work we do on this planet.

One’s philosophy of work is laden with so many assumptions and positions (whether we’re conscious of them or not) that inevitably come through in our actions:

Is work primarily a vehicle to pay for our lives, or to fulfill us and advance our deepest missions?

Is it wiser to have work/life separation or integration?

Do we owe society the fruits of our talents and contributions toward a common good, or do we mainly just owe ourselves and our families?

How do we want to engage our minds throughout our lives?

Do we care about getting really good at something—refining mastery and craft over time—or are we happy to just competently do our jobs?

We drift into work, jobs, and careers without really, in a disciplined way, asking ourselves fundamental questions that could transform how we experience those thousands of professional hours (and what we contribute from them).

For me, today’s artifacts made the ball easier to hold.

Where we’re heading:

“For anyone trying to discern what to do with their life, pay attention to what you pay attention to. That’s pretty much all you need.” — Amy Krouse Rosenthal

“Men are not free when they are doing just what they like… Men are only free when they are doing what the deepest self likes.” — D.H. Lawrence

“Do the work your soul must have.” — Katie Cannon

1. Who You Are | Parker Palmer, Let Your Life Speak

My favorite piece of career advice is this:

“The deepest vocational question is not ‘what ought I to do with my life?’ It is the more elemental and demanding ‘who am I? What is my nature?’

Before you tell your life what you intend to do with it, listen for what it intends to do with you.”

This feels so right, yet I had to confront a bunch of objections3 before I could really entertain it.

I could never really ground myself in more conventional career advice because it points to things that feel negotiable:

What problem do you want to solve? What does the world need? (There are countless problems worth solving, many of which I can imagine caring about.)

What do you want to do on a daily basis? Who do you want to be around? (There are plenty of people and activities I enjoy, and I expect that list will grow with time.)

What are you good at? What's your passion? (I have lots of interests and can probably develop skills in lots of directions—which of them should I focus on?)

What kind of life do you want? (A happy, peaceful, connected one!)

These questions are based on current preferences (what I like or have tried), or intellectual construction (what I should care about). They’re certainly worth considering, but I can’t trust their guidance if I just take each one in isolation; they’re only really helpful if they’re grounded in something I can’t talk myself out of (who I really am).

Parker Palmer, who writes more coherently about vocation than anyone I’ve read, has us discovering our vocation by looking at our whole life for evidence of a deeper nature which is more enduring.

“I must listen to my life and try to understand what it is truly about—quite apart from what I would like it to be about—or my life will never represent anything real in the world, no matter how earnest my intentions.”

When I’m feeling small, it feels naive and indulgent to aim for this kind of alignment. But when I’m feeling large, it feels both like my birthright and like one of the wisest things I could pursue. Aligning my deepest interests with my career would be a long-shot, a luxury, a pipe dream—but shouldn’t I at least try?

2. Your North Star | Susan Cain

Susan Cain offers a metaphor that reminds me of Palmer’s line of thinking:

“Your North Star is the longing that pulls you—the thing you must do, the thing that feels essential to your being . . .

Often the signs pointing to your north star have been with you all along—you just have to pay attention to them . . . [and] remember who you were as a child.”

As soon as I heard about the North Star, I knew mine. And I started seeing it reflected everywhere in my life: the art I like, the conversations I like, the things I reach for when I want to feel grounded, the activities that bring me into flow.

A North Star is the stuff that you naturally gravitate toward, that you love talking about, that you’ve been doing or thinking about since your youth. Cain suggests that identifying it can give coherence and guidance to your life. It did for mine.

To live a more aligned life, Cain recommends committing to core personal projects that point to your North Star. I love personal projects; they’re like little rebellions against the machine. (This newsletter is a core personal project; it takes a lot of time to write, and I wouldn’t give up the work for any amount of money!)

“Our core personal projects are . . . fundamental to our identity. They give our lives meaning and emotional weight.” — Brian Little

Look to the bottom of this post for North Star prompts!

3. Your Right Hill | Chris Dixon

I’m drawn to this idea of a life’s work: of playing a long-term game, getting better and better at something, and being on a trajectory.4 And that kind of requires finding the right hill.

Imagine an open landscape with many hills. Each hill is a different career—medicine, carpentry, farming, politics, teaching, acting, law, etc.

Chris Dixon offers some simple advice: make sure you’re on the right hill.

It doesn’t (ultimately) matter if you’re making great money or have an impressive title—if you’re on the wrong hill, it’ll eventually show up in your life as dread and disconnection. (And if you're thinking "ope, I'm probably not on the right hill or working toward my North Star, I just have a regular job that I don't love...” that's so normal! You can start small personal projects to experiment on other hills—if you want to.)

The rightness of your hill matters because:

climbing has opportunity cost (for your joy and development). On the wrong hill, you’re not absorbed in work you love to be doing, learning what most excites you, or developing the expertise you care about most.

climbing has opportunity cost (for your relationships and general well-being). On the wrong hill, you’re not building your most authentic network. And for many of us, our friends and community determine the quality of our support system, the opportunities that become available to us, and the majority of how life unfolds.

climbing the wrong hill can be painful. Especially if you aren’t inspired by the peak5 you’re heading for, or have been confronting the fact that no amount of hard work can make the wrong hill the right hill, or sense that you should be somewhere else, or are aren’t performing well because your work is misaligned.

on the right hill,

you can make decisions with clarity—about the relationships you build, the questions you ask, the work you say yes to, the boundaries you set, and the skills you develop.

you can speak and work from a sense of self, which leads to connections and collisions you can’t even imagine—of your favorite sort, because they’re focused on what matters most to you.

ambition is a process of becoming more fully yourself.

Dixon advises:

“Meander some in your walk (especially early on), randomly drop yourself into new parts of the terrain, and when you find the highest hill, don’t waste any more time on the current hill no matter how much better the next step up might appear.” |

4. Bullshit Jobs | David Graeber

”Without work, all life goes rotten.6

But when work is soulless, life stifles and dies.”

— Albert Camus

David Graeber masterfully describes what it’s like to be in soulless, stifling work:

“If you work 40 or 50 hours a week on tasks you secretly believe are not really necessary, how could this not have a deep psychological effect?”

It’s “what Mark Fisher refers to as ‘internalizing and reproducing nonsense, pretending it’s meaningful.’”

“Huge swathes of people . . . spend their entire working lives performing tasks they secretly believe do not really need to be performed. The moral and spiritual damage that comes from this situation is profound. It is a scar across our collective soul.”

I know when work feels like bullshit.7 And when you know it deep down, no matter what stories you (or your leaders) make up to justify it, the truth haunts you.

Graeber makes the provocative point that if you don’t adore your work, you’re still in survival mode.

“[Survival] is the starting point for most people. That point when you haven't begun to pursue your own path in life. All you know are the goals you've been assigned and what that worldview has allowed you to notice and learn.”

“We drown in survival mode . . . Wake up, go to work, deal with the boss, eat convenient foods because you don't have the time, skip the good habits you promised yourself you would do because you don't have the energy, watch your life slowly crash as your mind, body, and relationships unravel into chaos, and do nothing about it because it's the only life you know.”

So, he pushes us:

“There doesn't seem to be a higher priority than to create, build, design, write, sell, invest, own, experiment, and discover a way to control what you do with your day.”

In the same vein, I find use in Jerry Colonna’s concept of “working from an empty vessel.”

This is when you work without real grounding, experience, or conviction in your subject area. When you’re regurgitating what you’ve heard and mimicking passion and perspective you don’t actually have.

By contrast, working from a full vessel means drawing on the depth and wisdom of your lived experience, sharing what you’ve tested, wrestled with, and know to be true.

(Gut check: does most of your work come from the fullness of your vessel?)

5. Your Potential | Simone

In 2023, I found myself outside of a brewery in Paris, having the kind of conversation that’s easiest with a stranger. I was talking to a deeply accomplished artist, Simone, about his commitment to pursuing his craft and finding out what he’s capable of.

Eventually, he looked at me and asked non-rhetorically: “and you—what are you capable of?”

It was a breath of the freshest air. (Growing up as a young woman in the Midwest, I rarely felt pushed professionally or academically, save for a few incredible professors.8 Sometimes I even felt discouraged when I expressed ambition—people often reminded me that I didn’t need to chase bigger dreams, or that ambitions tended not to be all they’re cracked up to be.)

That night in 2023, surrounded by Parisian energy, I liked being asked: “where are you on your professional trajectory? Are you proud of it? Are you reaching your potential?” It reminded me of visions of myself that I’d forgotten. It reminded me that I can, and want to, engage in deep concentration and work hard at problems I’m obsessed with. If it’s true that “satisfaction lies in the effort, not in the attainment” (Gandhi)—and I suspect it is—then neither the attainment of money nor even expertise is the best part of work; it’s the process of working, learning, and practicing (the effort).

Simone asked about my best effort and urged me toward it. Now I’d like to sincerely ask you: what are you capable of?

“We must make the choices that enable us to fulfill the deepest capacities of our real selves.” — Thomas Merton

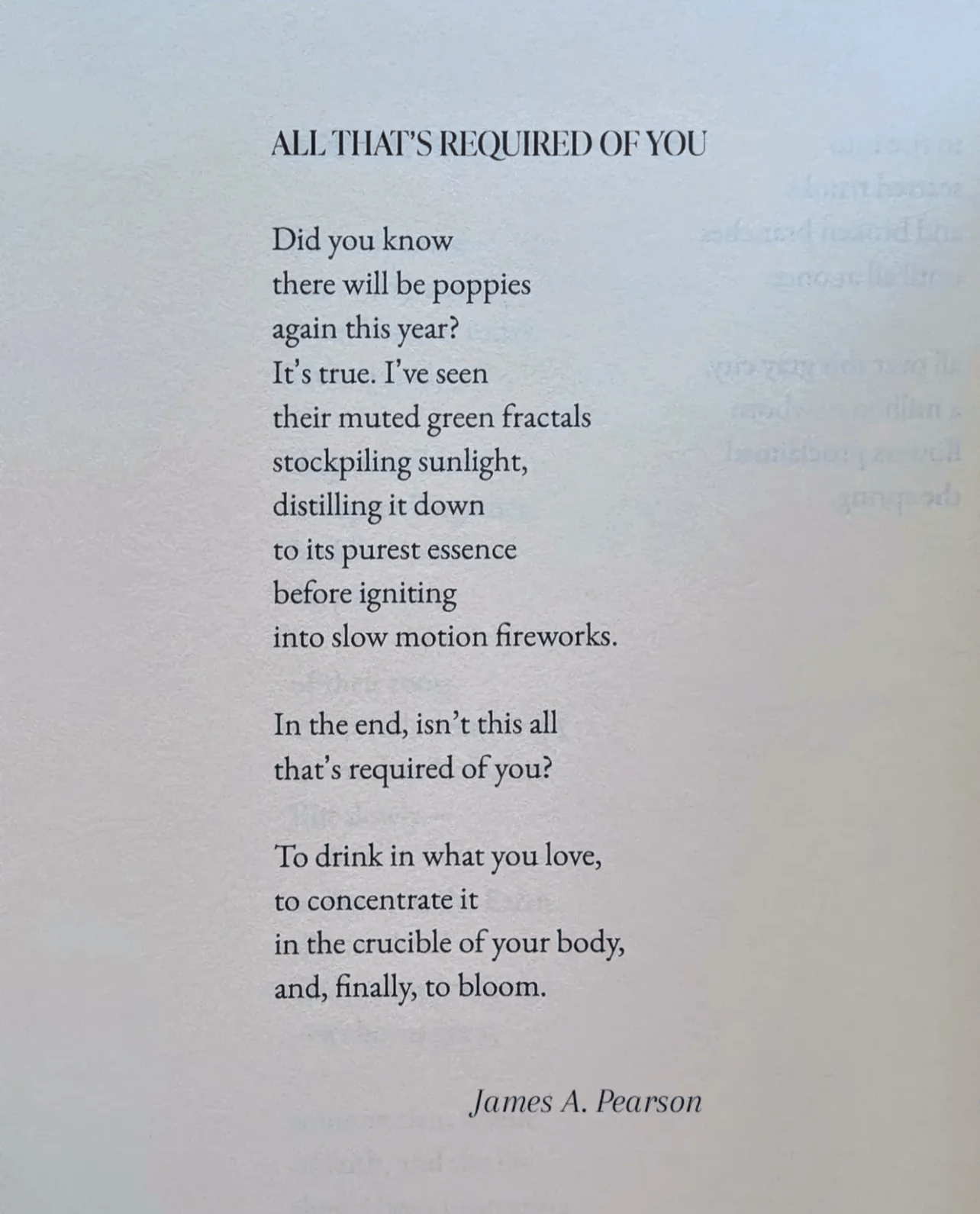

Okay. Say you do your best to:

listen to your deepest vocational desires

imagine creative ways of bringing them to life

take some serious steps in their direction (without even quitting your job!).

What more could you ask of yourself? That alone would be more than most of us do. That alone might be enough to ward off future regret.

If you have a quiet hunch about what you most want to do, can you imagine sincerely looking at your 90-year-old self and saying “I’m sorry, I couldn’t explore it”? Whatever barrier comes to mind, is there definitively no way around it? Isn’t your life worth the shot?

Wouldn’t it be bizarre to reach the end of your life and realize you never did the work to discover, or pursue, your life’s work?

C.S. Lewis

Take your thoughts outside ☀️🍃

Is my current work a deep expression of who I am?

Am I getting development in the areas I care about most?

Do I have long-term ambitions in the area I’m working in?

Am I living divided? What in my inner life wants to get honored in my outer life?

What do I naturally pay attention to and find myself doing?

What topics am I most drawn to?

What questions am I obsessed with?

What work feels most natural to me? Most native to my way of being in the world?

What work engages my soul more than any I know?

What craft do I take pride in? Experience a strong sense of personal identity in?

What do I care to be excellent at?

Whose ranks do I want to be amongst? Who do I want to be personal friends with?

What would I want to create in the world to support my younger self?

What would I be sad to never have worked on in my lifetime?

What was I simply born to do?

If my life was a movie and I was the main character, what would the audience be screaming at me to do?

For some unknown period of time, I get to inscribe something in my part of the universe. What do I want that to be?

1 Work sits at the intersection of so many competing forces: practical needs, social expectations, personal meaning, creative expression, financial security, identity formation. When I try to focus on what I really want, some consideration pulls my attention away. An objection, question, or distraction. And maybe such forces unavoidably shape our lives. But maybe there’s value in reflecting on them, so they don’t lull us away from a more intentional, authentic life.

2 There are life domains for which the conventional code or script makes sense. But there are domains where the script is woefully ill equipped to yield the life you want—and here, you need to exercise self-discernment, imagination, and courage.

3 I needed to wrestle with all of these before I could allow myself to simply imagine a career that is deeply aligned with who I am.

But your job doesn’t have to be the place where you experience or express your interests. True. But I do want to spend my life doing the work (paid or not) that I enjoy most, and paid work will take up much of my life, so to state the obvious, I want much of my paid work to be what I enjoy most.

But you’re not entitled to a perfect job. True. The world doesn't owe me a career that aligns with my passions and nature—but I might owe it to myself to try for one! And, in fact, the responsibility may flow the other direction: it might be I who owe it to the world to take a swing at discovering what work makes me happiest, which may be what I have most to offer.

But you’re lucky to have any work at all. Basically true. In this unpredictable, cosmic dance, it’s a huge gift to have stable resources. Especially if those resources come from work we don’t mind, with people we like, a flexible schedule, a comfortable office, and the ability to ‘turn off’ at 5pm. Having some money and some free time is more than many are afforded! (And it’s okay to attempt to get even more from your work and time.)

But it’s a privilege for your work and life to feel integrated. True. It assumes the conditions to not just work for survival, to be exposed to the right people and opportunities. Many people don’t have great options. Aligned work is a privilege! That doesn’t mean that it isn’t the best possible situation for our working lives, or that we shouldn’t go for it.

But what if there’s important work that no one wants to do? A true concern. But all I’m arguing for here is that there’s good reason to work on problems I really care about and feel naturally engaged in—isn’t it just true that, if I’m not loving or engaged in my work, I won’t do a very good job of it? So unless we’re arguing that I should try to adapt my preferences to the work that the world needs most (maybe I should??), I think it makes sense to pursue engagement with my work to also maximize my contribution.

But not everyone can prioritize professional alignment. True. Self-discovery requires mental and emotional resources, and self-actualization takes a lot of courage, and support, and risk. Your attention may be needed elsewhere, and if questions about your most authentic work feel overwhelming, this probably isn't the time to dig into them.

4 How very strivey.

5 Not that this is about picking the hill with the most attractive top. It’s about picking the better hill (for you) overall. If you don’t love climbing your current hill nor what’s on top, what are you doing on it? For how long?

6 Yes. I don’t fear a life centered on work (I think my happiest self is deeply absorbed in work); I fear a life centered on the wrong work.

7 This takes a big toll on me. I feel fraudulent. I move through the motions, focused on simulating the minds of other people so I can understand what they want and expect, rather than inhabiting my own body and voice. Eventually, dissociation and apathy set in. And when they do, the best I can do is to try to access myself: wait a second, what do I really think, want, believe, or need here?

I don’t want to role-play or pretend. I want to work with integrity: to be clear on what problem I’m solving, why I believe it’s among the most important problems to be solving, why I’m using a particular approach (because it’s well-tested or the smartest experiment I can think of), and why I’m the right person to do it.

I want to tell the truth at work, and everywhere. To spend my time on work because I believe in it. I want to feel so strongly about my work that I’d recommend it to others—that I could make a strong case for it. I want to be real with people. To feel real and to be real.

8 Mr. Davis wrote to my high school class:

“Theoretically, school is supposed to help students prepare for the future. Practically, I’m not so sure it always does. In his book On Paradise Drive, David Brooks argues that our schools—even the best of them—have become nothing more than ‘Achievatrons’—giant education machines designed to crank out easily measured chunks of success, and while success of any kind should be welcomed by all, this success tends to reflect nothing more than small mission, small vision, small hopes, and small dreams.”

I hear the warning, and I want big mission, vision, hopes, and dreams. Of my own variety.